My oath lasted one week. The next milk run to check cameras, and, you guessed it, there he was. Same plot. Same domination of younger bucks nearby. Same indifference to the camera. I emailed the series of pics to my hunting buddy Alan with a note: “He’s back. Where was he all summer?” Alan’s reply led to the buck’s nickname. “Wow. Nice stranger to have in the neighborhood!” So the name stuck. And so did the deer. Suddenly, he was popping up in front of cameras across the farm; early morning crossing the Imperial Whitetail Clover, middle of the night in the beans and just after dark in a plot of Pure Attraction.

As a rule, I try not to let an individual buck get under my skin. I recognize mature bucks for the survival machines they are, and I acknowledge myself as the bumbling idiot that I am. So I generally take a shotgun approach when goal-setting. I run through my pre-season cam pics and ogle a handful of bucks I’d be proud to tag. Then I leave the door wide open for any slightly smaller buck that might trip my trigger on a given day, and, of course, am completely susceptible to any newcomer.

But a one-buck-or-nothing campaign? I try to leave those to the good hunters. But dang that Stranger Buck. Suddenly, I was zipping through trail-cam pics looking only for him. Closing my eyes at funny times of the day and picturing little details of his rack. And, of course, sitting in tree stands on that farm and willing him to appear. But the pre-rut slipped by, and the chaos of peak breeding passed and not one good buck had dawdled past my stands, let alone the Stranger.

Suddenly, it was December, full of cold and snow, and just when a smart man would have given up, I found myself getting excited about that deer. The farm he called home had almost zero cover — the neighboring, off-limits property had all that — but we had all the food. And I’ve even seen the oldest, smartest, biggest bucks abandon caution when all they care about is a belly empty after a month of chasing does and avoiding hunters. If I played it smart, got in and out of stands carefully and waited for the perfect winds, I believed I had a good shot at the buck that had wriggled under my skin despite my best attempts to ignore him.

Everything lined up on a frigid December day just after Christmas. The temp was below zero, the winds out of the northwest felt like cactus needles, the snow ankle-deep and fresh. I knew two food plots were getting hammered by deer, and both were in the Stranger’s wheelhouse. I left the house at noon, planning a quick scouting run to both plots, hoping to find a clue leading me to the best place for the evening hunt.

When I pulled up to the first plot, I saw a clue, but not one I was expecting. Bald eagles are a beautiful bird, but when they roost in a tree in the middle of the day, miles from water, they are nothing but a carcass marker. This can be a great thing if, for example, you’re tracking a deer you’ve shot and can’t locate. Or it can be very bad, if the eagle is watching something dead that you don’t want to discover.

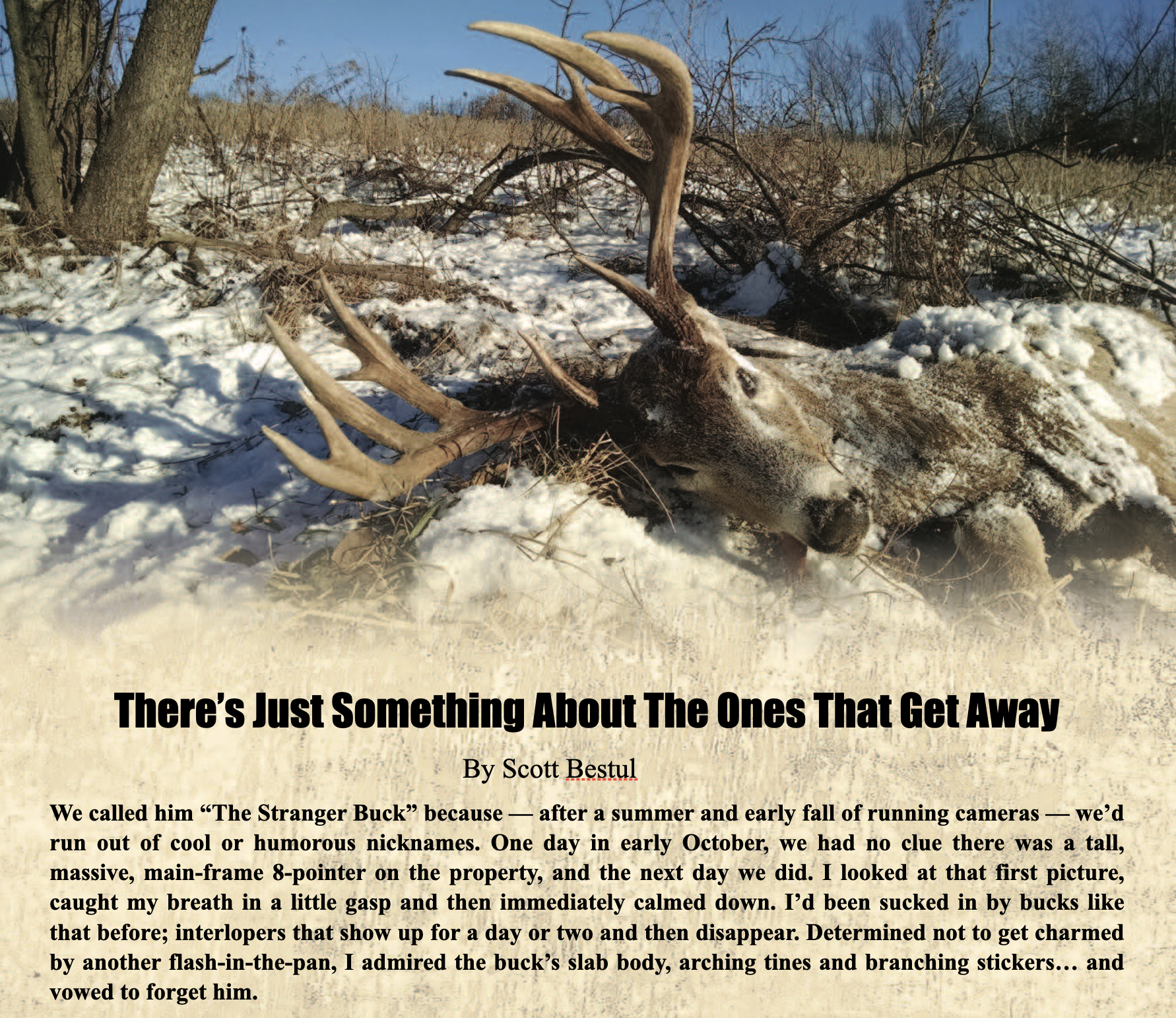

I was 50 yards from the truck when I spotted the tine; a long, bladed point with a sticker off it that I recognized immediately. Tangled in grass and brush, the rest of the rack came free after a couple of hard tugs, followed by the emaciated body of the Stranger. I found no visible wound on him, but his ribcage poked from his hide like a framework, and his spine stuck up like a series of mountain ridges. His front leg was broken, and I wondered how long an old, strong survivor like that could limp around after being hit by a car or battered by another buck. Long enough, apparently, to turn into little more than a skeleton covered by hair. The Stranger had beaten me. But at least he’d done me the honor of dying in a place where I could find him and acknowledge the defeat.

What is it about the bucks that get away? Sometimes, I have to visit my man-cave to recall a buck I was lucky enough to tag. But the big ones that kicked my butt? I can tell you every detail about them. My first sighting. Not only the shape of the rack, but every little kicker and quirk. This trail-cam pic and that close encounter. The nights I lay in bed, thinking of some new strategy for setting up that one ambush or stalk that would reduce him to my possession. And you’d think when my failure was complete — that another hunter did what I couldn’t, or the buck succumbed to disaster or simply disappeared — that I could forget them. Not a chance. Every buck that has whipped me is burned in my psyche like they’ve been soldered there. I’m not alone in this condition. My friend Bob Borowiak has killed some giant bucks, with a consistency that anyone would envy. But ask him sometime about “Lefty,” a buck that grossed more than 200 inches and was 6-1/2 years old when another hunter took him with a muzzleloader. Bob hunted that buck for three seasons and, during the summer before Lefty’s demise, had more than 1,000 hours of scouting invested in that buck, including summer filming sessions when the velvet-clad Lefty stood less than 50 yards from my friend.

Or talk to my friend Randy Flannery, a legendary Maine tracker who walks big, old deer down in wilderness hunts that can last for days. Randy has some fantastic bucks to his credit, but this past summer, I asked him about memorable ones that had given him the slip. He didn’t hesitate for a second in recalling a buck he and friend Dick Bernier trailed for an entire day, and one that challenged the finely honed skills of both men by jumping off a small cliff and then making a huge circle that led back to its original bed. The two experts finally admitted defeat after that last maneuver. Flannery’s son killed the buck the next fall.

Then there’s Ohio’s Adam Hayes, a man who’s likely killed more B&C bucks with a bow than anyone, including three that score more than 200 inches. Just this past summer, Adam was telling me about a gigantic 170-class 8-pointer that had gotten under his skin. The buck lived on a small farm that has room for only one stand, but Adam was confident the buck would swing past it after a few hunts and the deer would be his. Despite sitting the stand dozens of times in ideal conditions, Adam saw the buck only three times during Ohio’s long archery season — and he missed the only shot the buck gave him.

Then there’s Ohio’s Adam Hayes, a man who’s likely killed more B&C bucks with a bow than anyone, including three that score more than 200 inches. Just this past summer, Adam was telling me about a gigantic 170-class 8-pointer that had gotten under his skin. The buck lived on a small farm that has room for only one stand, but Adam was confident the buck would swing past it after a few hunts and the deer would be his. Despite sitting the stand dozens of times in ideal conditions, Adam saw the buck only three times during Ohio’s long archery season — and he missed the only shot the buck gave him.

The common ground between these tales (and others like them; I’ve talked to dozens of whitetail fanatics about this topic) is a deep and unbridled respect for the buck. In situations where another hunter tags the deer, there is no jealousy, resentment or bitterness — only a bemused acceptance that sometimes, no matter how good we are (or think we are), the bucks are usually better.

This is a truth that can be easy to forget these days. Outdoor television is packed with hunts for monster bucks that have been named, photographed and harvested in a 20-minute show that runs like a highlight reel. Big whitetails hit social media minutes after they hit the ground, deluding the average hunter into thinking that killing big deer is something that happens almost daily. I’ve been guilty of contributing to the craze as well, writing and photographing successful hunts and hunters while often ignoring all their fruitless hours and failed attempts.

Failure might not make much of a story, but it’s an integral and important part of deer hunting. Whitetails are animals of tremendous mystery; despite the broad base of knowledge we have now that primitive hunters — and even men who chased deer only a few decades ago — never had, we will never learn all we need to make deer hunting easy. No matter how many trail cams we run, food plots we plant, tree stands we hang, or hours we scout, track, drive, the mature whitetail buck will always have the edge.

Hunting, by its nature, is supposed to be a challenge, and, of course, we should celebrate every success. But it’s equally critical that we enter the deer woods with a keen sense of humility and respect. We should stand in awe of mature bucks; their incredible talent for survival and the gauntlet they have to run to reach old age. The bucks that elude us are there to teach us those lessons, and I treasure each one.